Leonardo da Vinci and Bartolomeo Marchionni

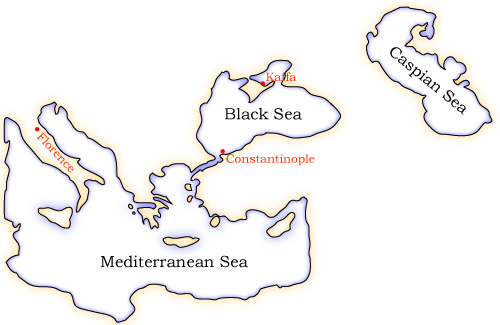

Leonardo da Vinci jotted down in one of his notebooks the following reminder: “Write to Bartolomeo the Turk as to the flow and ebb of the Black Sea, and whether he is aware if there is such a flow and ebb in the Hyreanean or Caspian Sea.”(i) According to Ritter, who was the original translator of Leonardo’s notebooks, the handwriting indicates that the note was written during the latter years of his life. I have checked many publications including recent ones relating to Leonardo and his life but no one appears to have identified Bartolomeo the Turk. Leonardo’s comment indicates that:

- Bartolomeo the Turk and Leonardo da Vinci lived in different towns.

- Bartolomeo the Turk was familiar with the Black Sea but not necessarily the Caspian Sea.

- The name Bartolomeo is a fairly common Latin name, but Leonardo’s spelling of the name is Italian. The name is spelt Bartolome in Spanish and Bartolomeu in Portuguese. Although Leonardo did not pay too much attention to spelling, it is likely that the person he was referring to was Italian.

I would like to propose, for the reasons given above, that Bartolomeo di Domenico Marchionni, scion of the Marchionni family,(ii) was Bartolomeo the Turk. Bartolomeo Marchionni had the patronym Domenico. Another of Leonardo’s friends, “Fioravante di Domenico at Florence is my most beloved friend, as though he were my brother”(iii) had the same patronym. Is this a coincidence or were Bartolomeo and Fiorvante brothers? This observation could possibly be confirmed by consulting the archives in Florence for a frame around 1470, to determine whether two brothers in the Mardhionni family had the names, Bartolomeo and Fiorvante.

Bartolomeo Marchionni, who became the wealthiest banker in Lisbon, was a major trader in West African slaves and was known in Lisbon as Bartholomeu Florentim.(iv) From around 1360 his family were prominent traders in Kaffa (now known as Feodosia), the Genoese dominated city, on the Crimean peninsula on the Black Sea.(v) The economy of Kaffa was based on trading of slaves, musk, gold, ivory and spices. The Marchionni family imported slaves, mainly females, into northern Italy to work as domestic servants. In this connection it is interesting to note that Alessandro Vezzosi, the director of the Museo Ideale Leonardo da Vinci, has concluded that da Vinci’s father was a minor nobleman or craftsman named Ser Piero da Vinci, while the artist’s mother was a Middle Eastern slave, known by the name Caterina. Leonardo was left-handed, but began all of his notebooks on the last page, which was customary for Arabs and Jews.(vi) Is it possible that the Marchionni family sold Caterina to Leonardo’s father?

Constantinople fell to the Ottoman Turks in 1453. This did not prevent the Marchionni family from continuing their slave trading operations in Kaffa, as they still had at least one representative there in 1462.(vii) Kaffa came under Turkish rule in 1475, ending all European trade in the region. This association with the Turkish conquest of Constantinople and the Black Sea and the slave trading activities of the Marchionni family in Kaffa could have earned Bartolomeo Marchionni the nickname “Bartolomeo the Turk.”

Sergio Tognetti, a contributor to the book Black Africans in Renaissance Europe, has stated that prior to 1470, Bartolomeo Marchionni lived in Florence with his family who owned an apothecary shop that overlooked Brunelleschi’s Basilica of San Lorenzo (location #1).(viii) Spices were a valuable commodity in the 15th century, often worth their weight in gold, and were among the items obtainable from Kaffa on the Black Sea. Owning an apothecary shop/spice shop would be a logical addition to the slave trading activities of the Marchionni firm. At the same time, Leonardo’s father was living on the Plaza Signoria (location #5) and had an office opposite the Bargello (location #4), both within a few blocks of the apothecary shop owned by the Marchionni family. Verrocchio’s bottegha, where Leonardo was an apprentice, was also close by.(ix) In 1470 Bartolomeo Marchionni was fifteen years old, two to three years younger than Leonardo da Vinci. The two teenage boys may have known each other. Judging by their addresses, both families were among the Florentine elite.

The occupation of Kaffa by the Ottoman Turks ended the slave trading activities of the Marchionni family. Bartolomeo Marchionni left Florence in 1470 and went to Lisbon as an office boy to the Cambini family of merchant bankers and West African slave traders. He probably intended to transfer the family business to Portugal where the West African slave trade was in its infancy. By 1482, about the same time as the bankruptcy of the Cambini Bank, Marchionni was well established as a merchant banker in Lisbon, with sugar plantations in Madeira. He was also becoming a major player in the West African slave trade.(x)

The possible association of Bartolomeo Marchionni with Leonardo da Vinci extended to having mutual friends and colleagues in common. Marchionni worked with Benedetto Portinari in Lisbon and had a business relationship with Tommaso Portinari who managed a branch of the Medici bank in Bruge from 1473-1481. In 1474 or 1475 Marchionni and the Portinari brothers used money from this bank to finance an unsuccessful voyage to obtain gold from West Africa.(xi) This was probably the ill-fated Flemish ship that in 1475 was wrecked off the West African coast on its return voyage to Bruge. The local inhabitants ate the crew and sold the gold to Portuguese traders the following year.(xii) Lorenzo de Medici and his bank absorbed all the financial losses resulting from the sinking of this ship. When the Medici Bank in Bruge went bankrupt in 1479, an audit of the books listed Bartolomeo Marchionni and Benedetto Portinari among its debtors. The bank was closed and Tommasso went to live in Milan.(xiii)

Leonardo’s life in Florence in the 1470’s was fraught with difficulties. He was twice accused of sodomy, and in 1481 he was not included among the painters selected to go the Vatican to assist in decorating the recently built Sistine chapel. Some time around 1482 to 1483 Leonardo left Florence for Milan. Here he met Tommasso and Benedetto Portinari who were both interested in painting, having had their portraits painted by Hans Memling, the Flemish painter. In his journal, Leonardo made the following notation: “Ask Benedetto Portinari how the people go on the ice in Flanders?”(xiv) Bruge was at that time part of Flanders. In 1487, Tommasso Portinari became an ambassador to Ludovico Sforza of Milan, representing Maximillian I of Austria. He may have helped Leonardo obtain work at the Sforza court.

Leonardo also had a close relationship with Benedetto Dei, a representative of the Portinari family, who in 1470 was the first white man to visit Timbukto. Leonardo wrote Benedetto Dei a lengthy letter about bringing him “news from the East” and of “a giant appearing from the Syrian Desert.”(xv) Dei is known to have been in Milan between 1484-87, but Leonardo may have met him earlier in Florence through his association with Paolo Toscanelli with whom Dei was very friendly.(xvi) Leonardo referred to Toscanelli as Maestro Paolo the physician.(xvii) It can also be shown that Marchionni knew Toscanelli, the renowned astronomer, physician, geographer. The eulogy Marchionni gave to King Manual of Portugal credited Toscanelli with influencing Portugal’s nautical activities.(xviii) These mutual acquaintances may have helped maintain Leonardo’s and Bartolomeo Marchionni’s boyhood association, assuming they had one.

With the impending invasion of Milan by the French and the subsequent downfall of Ludvico Sforza, Leonardo was forced to leave Milan during the last days of 1499. He was again confronted with adversity. Meanwhile Marchionni was going from strength to strength. He helped finance the Portuguese voyages to India and the Orient. His caravel, the Santiago, sailed for India with Vasco da Gama’s fleet in 1497, returning in September 1499 with a cargo of spices.(xix) Isabella d’Este was aware of a letter Marchionni wrote to friends in Italy concerning this expedition. Around this time Leonardo visited Isabella d’Este in Mantua and made a half-length portrait drawing of her that now hangs in the Louvre. Perhaps he was present when this nautical triumph of da Gama was being discussed.(xx)

In 1502, while in the services of Cesare Borgia, Leonardo apparently offered his services to Sultan Bejazer II to build a bridge at Constantinople over the Golden Horn. Needless to say the bridge was never built. The note relating to Bartolomeo the Turk was apparently written during Leonardo’s later years and probably had nothing to do with Leonardo’s contact with the sultan.(xxi)

Marchionni owned one of the ships that sailed with Cabral in 1501 that resulted in the accidental discovery of Brazil.(xxii) He probably engineered and financed the subsequent expedition to Brazil that included his friend and fellow Florentine trader and explorer, Amerigo Vespucci. Vespucci’s letters to his patrons, Lorenzo di Pierfrancesco de’ Medici (Lorenzo de’Medici’s cousin) and Piero Soderini (the governor of Florence) described his voyages to this New World. These letters convinced the Europeans that a new continent had been discovered. Leonardo was acquainted with Amerigo Vespucci.(xxiii) and Vasari claims that there was a sketch of Amerigo Vespucci in Leonardo’s book of drawings.(xxiv)

Leonardo returned to Milan in 1506, where he worked until the unrest in Milan again forced him to leave in 1511. From 1513 to 1516, Leonardo, now over sixty, worked for the first time in Rome under the patronage of Guliano de Medici, the youngest son of Lorenzo de Medici. While in Rome, Leonardo lived in an apartment at the Belvedere, a summer palace outside the Vatican and near the papal palace.(xxv) Hanno, the albino elephant from India, was living in the courtyard of this palace during Leonardo’s stay. This elephant was a present to Pope Leo X (Giovanni de Medici, the middle son of Lorenzo) from King Manuel of Portugal. There appears to have been a good relationship between the two younger sons of Lorenzo and the Portuguese throne. Bartolomeo Marchionni was still sending representatives, generally Florentine associates, with the Portuguese on voyages to India.(xxvi) In 1515-16, Giovanni of Empoli, an employee of Marchionni and Andrea Corsali, a Florentine merchant and explorer, both sent letters to Guliano de Medici in Rome describing their travels. In a letter dated 1515, Corsali wrote the following: “a gentile people called Guzzarati who do not feed on anything that has blood, nor will they allow anyone to hurt any living thing, like our Leonardo da Vinci, they live on rice, milk and other inanimate foods.”(xxvii)(xxviii) Guliano de Medici died early in 1516 and Leonardo left Rome later that year, so it is not clear whether either of them actually saw these letters.

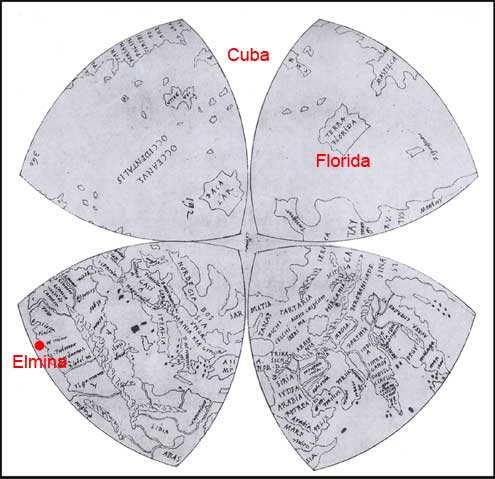

A map showing details of the Northern hemisphere, was found among Leonardo’s papers in the Windsor collection.(xxix) It was obviously drawn shortly after Ponce de Leon discovered the southeast side of Florida in 1513. Florida was initially, as this map indicates, assumed to be an island and only later was it realized that Florida was part of the North American continent. Of particular interest are the details given on this map of the West African coastline, including the position of the fort at Elmina, or Mina, where the Portuguese had located gold. It has been established that someone other than Leonardo drew this map, someone familiar with Portuguese activities in Africa, India and the Orient. Richter comments: “Leonardo’s researches as to the structure of the earth and the sea were made at a time, when the extended voyages of the Spaniards and Portuguese had also excited a special interest in Italy.”(xxx) Leonardo was very interested in countries in the East, but never mentions the discovery of America.(xxxi) If he saw the letters from Giovanni of Empoli and Andrea Corsali then this map may have been used to illustrate their travels.

The above discussion indicates the following:

- The Marchionni family who ran a slave trading organization in Kaffa on the Black sea, may have sold Leonardo’s mother to his father.

- Bartolomeo Marchionni was a couple of years younger than Leonardo.

- Prior to 1470, Bartolomeo Marchionni lived in Florence close to where Leonardo was an apprentice to Verrocchio. The two teen aged boys may have known each other.

- Bartolomeo Marchionni may have visited Kaffa during his youth thus earning him the nickname Bartolomeo the Turk.

- From about 1480 until 1516, Leonardo and Bartolomeo Marchionni had many friends and associates in common so it is difficult to imagine that the two men did not know of each other.

- Leonardo, who presumably had little or no experience in ocean travel, would have selected someone familiar with the Black and possibly the Caspian Seas, and who also had experience in oceanography, to provide him with the information he required from Bartolomeo the Turk. Bartolomeo Marchionni appears to have had the necessary credentials.

- Leonardo, based on his hand writing, jotted down the note referring to “Bartolomeo the Turk” in the later years of his life. From 1513-1516, his patron, Guliano de Medici, was in contact with one or more of Bartolomeo Marchionni’s employees and possibly Marchionni himself.

It is not possible to prove with one hundred percent certainty that Bartolomeo Marchionni was Bartolomeo the Turk, but it is certainly plausible that Bartolomeo Marchionni and Leonardo da Vinci were acquaintances. Leonardo may therefore have been in contact with one of the most influential merchant bankers of his time.

If it is accepted that Bartolomeo the Turk and Bartolomeo Marchionni are the same person, this observation could open up for investigation and debate new aspects related to Leonardo’s life. For example, what was Leonardo’s relationship to this wealthy merchant, banker, slave trader and friend of kings? Both these men were pillars of the Renaissance. The rich and powerful Bartolomeo Marchionni, who was influential in the Portuguese voyages of discovery, is all but forgotten. Leonardo da Vinci, who depended on patronage, is still greatly admired for his artistic genius and the depth of his intellect. One question that might be asked, is what affect if any did Marchionni have on Leonardo’s life? Did Marchionni, through his associates, help Leonardo gain access to the Sforza court in Milan and other wealthy patrons? Did he provide Leonardo with one of his first commissions to prepare the now lost cartoon of Adam and Eve, that was to be woven in silk and gold in Flanders as a door hanging for the King of Portugal? The tapestry was never made and Leonardo’s uncle gave the cartoon to Ottaviano de Medici.(xxxii) Did this relationship open additional avenues of income for Leonardo through the sale of artifacts in Africa or Asia? In 1493 Leonardo recorded that some of his workers were making candlesticks and locks in his workshop in Milan.(xxxiii)

- ↑ back Richter, J.P., 1970, The Notebooks of Leonardo da Vinci Vol.II, Dover Edition, New York, p.267 No.1105.

- ↑ back Thomas, H. 1997, The Slave Treade, Touchstone Books, New York, p.10-11 and 84-86.

- ↑ back Richter, I., 1980, The notebooks of Leonardo da Vinci, Oxford University Press, Oxford, p.289.

- ↑ back de Roover R., 1999, The Rise and Decline of the Medici Bank, 1397-1494, Beard Books, Washington DC, p478 no.4176.

- ↑ back Thomas, H. 1997, The Slave Treade, Touchstone Books, New York, p.42.

- ↑ back Viegas, J., Leonardo Da Vinci: Son of a Slave?, Discovery Magazine, 9-30-2002

- ↑ back Thomas, H. 1997, The Slave Treade, Touchstone Books, New York, p85.

- ↑ back Tognetti, S., 2005, Black Africans in Renaissance Europe, Ed. Earle, T.F. and Lowe, K.J.P. Cambridge University Press, UK, p.222

- ↑ back Nicholl, C., 2004, Leonardo da Vinci The Flight of the Mind, Penguin Books, London, p.64 and 73.

- ↑ back Thomas, H. 1997, The Slave Treade, Touchstone Books, New York, p.10-11 and 84-86

- ↑ back de Roover R., 1999, The Rise and Decline of the Medici Bank, 1397-1494, Beard Books, Washington, p349-.352.

- ↑ back Blake, J.W., 1942, Europeans in West Africa, 1450-1560 vol. I, Hakluyt Society, London, p. 207-8.

- ↑ back de Roover R., 1999, The Rise and Decline of the Medici Bank, 1397-1494, Beard Books, Washington DC, p.352.

- ↑ back Richter, J.P., 1970, The Notebooks of Leonardo da Vinci Vol.II, Dover Edition, New York, p.435, no.1448.

- ↑ back Richter, J.P., 1970, The Notebooks of Leonardo da Vinci Vol.II, Dover Edition, New York, p.271.

- ↑ back Nicholl, C., 2004, Leonardo da Vinci The Flight of the Mind, Penguin Books, London, p.194 and 216.

- ↑ back Nicholl, c., 2004, Leonardo da Vinci The Flight of the Mind, Penguin Books, p.148.

- ↑ back Gray, R. and Chambers, D., 1965, Materials for West African History in Italian Archives, Athlone Press, University of London, p.131, no.1275.

- ↑ back Thomas, H. 1997, The Slave Treade, Touchstone Books, New York, p.10-11 and 84-86

- ↑ back Kaplan, P.H.D., 2005, Black Africans in Renaissance Europe, Ed. Earle, T.F. and Lowe, K.J.P. Cambridge University Press, UK, p.139 footnote 51

- ↑ back Nicholl, c., 2004, Leonardo da Vinci The Flight of the Mind, Penguin Books, p.326-7.

- ↑ back Greenlee, W.B., 1967, The voyages of Pedro Alvares Cabral to Brazil and India, Hakluyt Society, , Kraus Reprint, Nendeln Ser II, vol..81, Liechtenstein, Second Series No. LXXXI, , London, p. 145-50.

- ↑ back Richter, J.P., 1970, The Notebooks of Leonardo da Vinci Vol.II, Dover Edition, New York, p.130 footnote 844.

- ↑ back Vasari, G., 1965, Lives of the Artists, Penguin Books, England, p.261.

- ↑ back Bramly, S., 1994, Leonardo The Artist and the Man, Penguin Books, London, p. 383

- ↑ back Greenlee, W. B., 1967, The Hakluyt Society Ser II, vol..81, The Voyage of Pedro Alveres Cabral to Brazil and India, Kraus Reprint, Nendeln, Liechtenstein, Second Series No. LXXXI, p.146.

- ↑ back Spallanzani, M., 1984, Giovanni da Empoli, , Firenze, S.P.E.S., p201 and p.21

- ↑ back Richter, I., 1980, The notebooks of Leonardo da Vinci, Oxford University Press, Oxford, p.382.

- ↑ back Vezzosi, A., 2000, Leonardo El’ Europa, Relitalia Studi Editoriali, p.101.

- ↑ back Richter, J.P., 1970, The Notebooks of Leonardo da Vinci Vol.II, Dover Edition, New York, p.173.

- ↑ back Richter, J.P., 1970, The Notebooks of Leonardo da Vinci Vol.II, Dover Edition, New York,, p224-5.

- ↑ back Vasari, G., 1967, Lives of the Most Eminent Painters, Vol I, The Heritage Press, New York, p.312

- ↑ back Richter, I., 1980, The notebooks of Leonardo da Vinci, Oxford University Press, Oxford, p.314..