The Voynich Botanical Plants

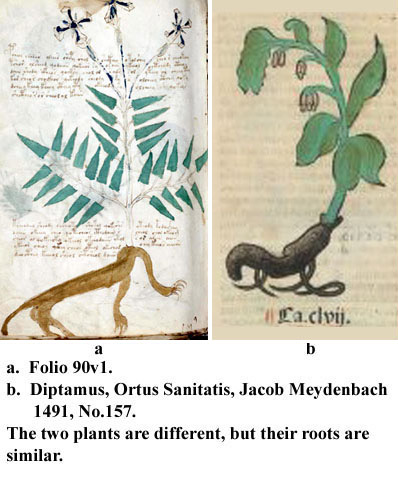

Botanists, who examined the VM’s botanical drawings, have dismissed them as a mishmash of flowers and leaves belonging to unrelated plants. The fanciful nature of some drawings makes identification with 21st century plants difficult. For example, one plant has a root system resembling a headless cat, another has leaves that look like a series of spears. The large number and variety of species in the plant kingdom further complicates the problem. The 18th century Linnean Herbarium contains over 14,000 plants classified into genera. The Ranunculus genus had 78 species; today, this number has increased to 600. Other members of the Ranunculaceae family include buttercups, spearworts, water crowfoots, winter aconite, monk’s hood and the lesser celandine. Their flowers may have a few, many or no petals at all and a variety of different types of leaves. The diversity of flowers and leaves within a genus and the magnitude of the plant kingdom, makes the identification of the VM’s botanical plants rather like looking for a needle in a haystack.

The botanical section of the VM may represent, in part, a private herbal. Consulting herbals used in the Middle Ages should help with the identification of these drawings. Pedanius Dioscorides (c. 40 – c. 90 AD) produced the first herbal. His simple, natural drawings, used to illustrate De Materia Medica, were the gold standard for herbal illustrations until about 1550 AD. The illustrations in many subsequent herbals are degraded, stylized reproductions of Dioscorides’ work. Fortunately, by the 15th century, herbal illustrations had improved. These illustrations were simple basic drawings of plants, often representing not much more than a twig with a few leaves and perhaps a few flowers. By the middle of the 16th century, botanists like Dodoens Pemptades, Fuch and Mattioli reintroduced naturalism and more complexity into their herbal drawings.

Digitized copies of 15th century herbal books and manuscripts, contemporary with the VM, are now available on the Internet. The simple woodcut illustrations in the herbal incunabula (books printed before 1500 AD) in conjunction with their Latin names, have allowed me to identify many of the VM’s botanical drawings.

I also used illustrations from the following two books:- Herbs, for the Mediaeval Household, Margaret B. Freeman, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 1943.

- Herbals, their Origin and Evolution, Agnes Arber, Cambridge University Press, 1938.

- Herbarius, Peter Schoeffer, 1484, in Latin., MGB Digital Library.

- Hortus Sanitatis, Peter Schoeffer, 1485, The only illustrations I could find from this herbal are from Margaret Freeman’s book, Herbs, for the Mediaeval Household.

- Gart der Gesundheit, Peter Schoeffer, 1485, Botanicus.internet site.

- Ortus Sanitatis, Jacob Meydenbach, Mainz, Germany, 1491. There are two copies of this herbal, one in black and white with easy to read Latin titles is available on the Smithsonian internet site, and a colored version on the Harvard University Library site.

- Herbarius Patauie Impressus, 1485, Harvard University Library site.

Some of the VM’s botanical drawings show a surprising similarity to woodcut illustrations in herbals, printed after 1484, using the Gutenberg Press in Mainz, Germany. One of the printers, Peter Schoeffer, was apprenticed to Gutenberg and after Gutenberg’s death, he continued printing his own books, publishing his first herbal in 1484. His herbals were printed in either German or Latin. It should be pointed out that Peter Schoeffer was just the publisher of these herbals; he probably did not write the texts. Printers of other herbals used many of his woodcuts. The author or authors of these herbals are unknown, likewise the origin of the woodcuts and who carved them.

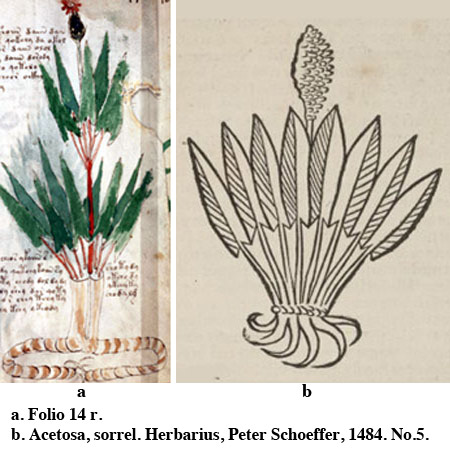

Examining these woodcuts caused me to postulate that many of the VM’s drawings were not drawn from nature, but were copied from a contemporary herbal or herbals with similar odd characteristics. VM folio 14r has leaves like spears and is very similar to the illustration of sorrel, in Peter Schoeffer’s Herbarium, Plate 1. The illustration of diptamus in Jacob Meydenbach’s Ortus Sanitatis has roots resembling a headless animal, similar to the plant, folio 90v1, that has roots like a headless cat, Plate 2. Other examples are given later. Nobody in the 15th century would have considered the VM’s drawings strange or unacceptable; they are no different from other 15th century herbal drawings.

What initially puzzled me was why some of the VM’s drawings appear almost identical to illustrations from herbals printed in Germany, from 1484 onwards. The VM is assumed to have originated in Italy sometime around the middle of the 15th century. Further investigation showed that some VM drawings closely resembled illustrations from the following Italian herbals:

- Herbal, N. Italy (Lombardy), c.1440, Sloane MS 4016, British Library internet site.

- Tractatus de herbis (Herbal); De Simplici Medicina, Bartholomaei Mini de Senis; Platearius; Nicolaus, between c.1280 and c.1310. S.Italy (Solerno). Egerton MS 747, British Library internet site. This manuscript provides English names with the plant illustrations.

- Herbarien des Pseudo Apulelus und Antonus Musa, & Essen 305, Fulda. C~1470. The small size of the illustrations made the print too small to read.

- Pseudo Antonus Musa. De Herba Vettonica Liber. Hartley MS 1585. Produced in the last quarter of the 12th century. British Library internet site. Antonius Musa was a botanist and physician to the Roman Emperor Augustus. His brother was physician to King Juba II of Mauretania (Libya).

Further investigation of the drawings of VM’s plants indicated that they could be divided into two basic groups, plants that were drawn directly from nature and those drawings that were very similar to or could be identified from illustrations in German or Italian herbals. Latin names were used to identify plants in the early herbals. If this name later became the botanical name of the plant, identification is simple. However if the two names are different, then correlating an illustration with a living plant is not always possible.

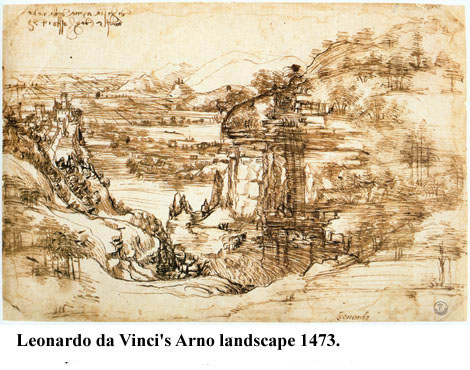

Many of the drawings of plants, I have dubbed drawn directly from nature, are alpine. I had the good fortune last year, while on a cruise down the Danube, of buying the following book: Alpen Pflanzen, text R.Slavik, illustrations j. Kaplicka, Artia, Prag, 1977. I realized, while thumbing through its pages, that I was looking at a number of the VM drawings, drawings I was unable to find counterparts for in the various herbals I had consulted. This observation probably indicates that the author of the VM lived in a hilly or mountainous region of Northern Italy, where the winters are cold, something like Leonardo da Vinci’s landscape drawing, dated 1473, of the Arno River, Plate 3.

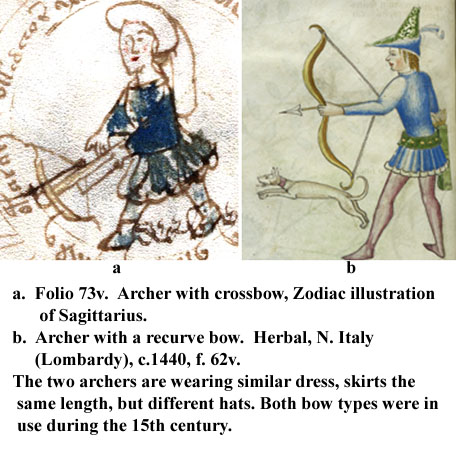

I am not sure whether I have simplified the mysteries surrounding the VM or further muddied the waters. Some people may conclude that this article confirms the hypothesis that the VM is just a forged document or that its author was a German. This is negated by the similarity in dress, except for the hats, of the archers in the VM’s zodiac Sagittarius folio and in the Sloane MS 4016, c. 1440 manuscript, Plate 4.

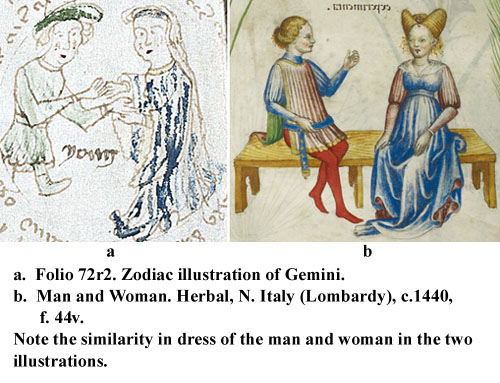

The dress of the man and woman in the VM’s zodiac Gemini folio and the Sloane MS 4016 manuscript are also similar, Plate 5.

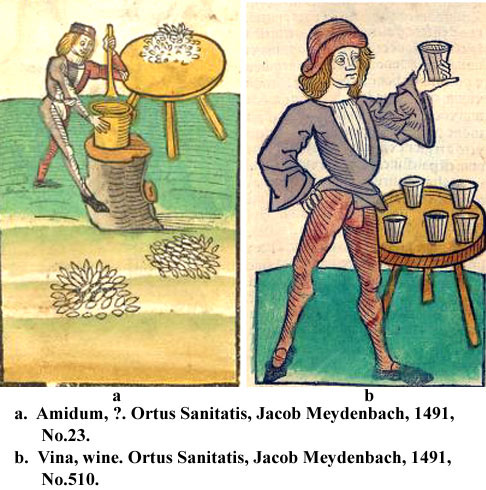

Later in the 15th century men’s skirts became extremely short, requiring the use of a codpiece, Plate 6. The fact that the VM’s male clothing and the recent C14 dating of its parchment, both date the manuscript to near the middle of the 15th century, makes the forgery hypothesis unlikely. The correlation of these drawings with an Italian herbal, c. 1440, probably excludes the hypothesis that a German was the author.

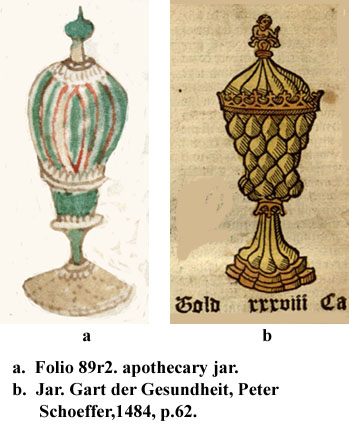

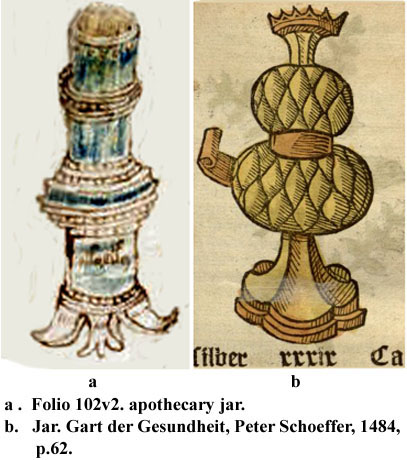

Plate 7 and Plate 8 show how similar two of the apothecary jars from the VM’s herbal section are to jars illustrated in Peter Schoeffer’s 1485 herbal, Gart der Gesundheit.

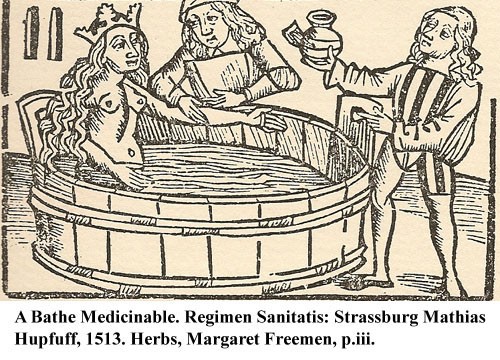

Anyone who has wondered about the nude little ladies sitting in wooden bath tubs in the VM’s astrological drawings should take a look at Plate 9. Judging by the attire of one of the attendants in this woodcut, who is obviously wearing a codpiece, this illustration was made about 50-60 years later than the VM’s drawings. It shows that wooden bath tubs were in use during the latter part of the 15th century and possibly earlier.

This investigation has produced a few surprises. Dried clove flower buds came exclusively from the Spice Islands of Indonesia. An accurate drawing of a clove tree in full bud, Egerton 747 c. 1300 AD, shows an accurate drawing of this tree, yet a few pages later the drawing of a coconut palm bears no resemblance to a palm tree. The VM’s drawing (Folio 27v) accurately depicts the clove tree’s white daisy like flower with an elongated calyx. The Arab traders, who used the silk road to supply the Mediterranean countries with herbs and spices, kept the source of their products a closely guarded secret, hence my surprise that the author of Egerton MS 747 knew what a clove tree looked like.

Another surprising plant is, caulis polygonii multiflori, an important herb, native to China. It is accurately illustrated in Jacob Meydenbach’s 1491 herbal. This vine with a large tuberous root could equally well substitute for Byrony (Folio 96v). After making several guesses regarding the identity of the infamous ‘sunflower’ (Folio 33v), I am satisfied that this folio represents the small plant, winter aconite, a member of the Ranunculaceae family. Winter aconite, like Folio 33v, has ‘tuberous roots, palmate lobed leaves, yellow flowers with large hood-like upper sepals and an aggregate of follicles.’ A good fit with Folio 33v. The VM’s drawings are not necessarily drawn to scale.

Not all the illustrations in these medieval herbals, like the case of the coconut palm, are correct. In addition, the Latin names given to some illustrations may not represent a 21st century plant with the same name. For example, there is an illustration in Ortus Sanitatus, labeled Sambacus, which is another name for elderberry. The sambacus flowers in this illustration look a lot like Folio 10v’s ‘twin flower,’ and nothing like an elderberry flower. Differences like this are part of the problem with the identification of the VM’s botantial drawings. Some drawings may represent ‘fictitious’ plants.

I was unable to find a herbal that represented all the VM’s odd characteristics or all its plants, even though some printed herbals listed about 500 plants. A few of the illustrations used in this article are from internet web sites whose URLs I failed to record. I was unable to identify Folio 90r1 or correlate it with illustrations in other herbals.

I have assigned the rest of the VM botanical folios to one or another of the following three categories:

- Drawings that are probably copies of illustrations found in other herbals

- Drawings that are similar to illustrations in other herbals

- Plants drawn from nature

With each folio I provide a brief description of how the plant was used during medieval times. A (*) indicates the source of the information was:

- Wikipedia

- Freeman, M., Herbs, for the Medieval Household, The Grete Herball, the English translation of Hortis Sanitatis and Bancker’s Herbal referred to in this book are not currently available on the internet

- Arber, A. Herbal

- Grieve, M, A Modern Herbal, Dover Publishers, New York